With productivity in construction a more acute problem than other sectors, Nigel Ostime of Hawkins\Brown says that architects need to embrace offsite Design for Manufacture and Assembly as the panacea which also delivers the quality they want

Productivity in the manufacturing sector has grown year on year, whereas in the construction industry it has been flatlining for decades. This poor productivity has reduced the margins needed to finance inward investment and improvement, compounding the poor value delivered compared to other sectors. The consequential lack of financial reward is also a disincentive for new entrants to the market.

Quality has been hobbled by lowest price rather than best value procurement, and through a lack of appetite for learning and improving through structured, post project completion review.

These issues pose an existential threat and should be addressed if we are to create a built environment that provides wellbeing, sustainability and growth.

Modern methods of construction

The building industry has been advocating modern methods of construction (MMC) for some time. Its benefits are known: it is faster, safer and often allows for better quality than traditional on-site construction due to its factory-led production. But take-up of MMC has been slow, particularly in the housing sector.

The difficulty is usually associated with a lack of capacity and the cost of entry into the market, as well as the stigma against modular building – whether for practical or aesthetic reasons.

Recently though, some big players have taken the plunge and invested heavily in modular housing, including L&G and Goldman Sachs as well as Japanese giant Sekisui. On the whole though, offsite construction is still seen as an ‘alternative’ to traditional methods, rather than a ‘business as usual’ approach.

Architects and other designers need to have a comprehensive knowledge of the offsite systems available and then select the right one for the specific site and building type.

The term pre-manufactured value (PMV) has started to be used to describe the percentage of a building that is pre-manufactured in a factory and brought to site for assembly, as opposed to traditional forms of construction.

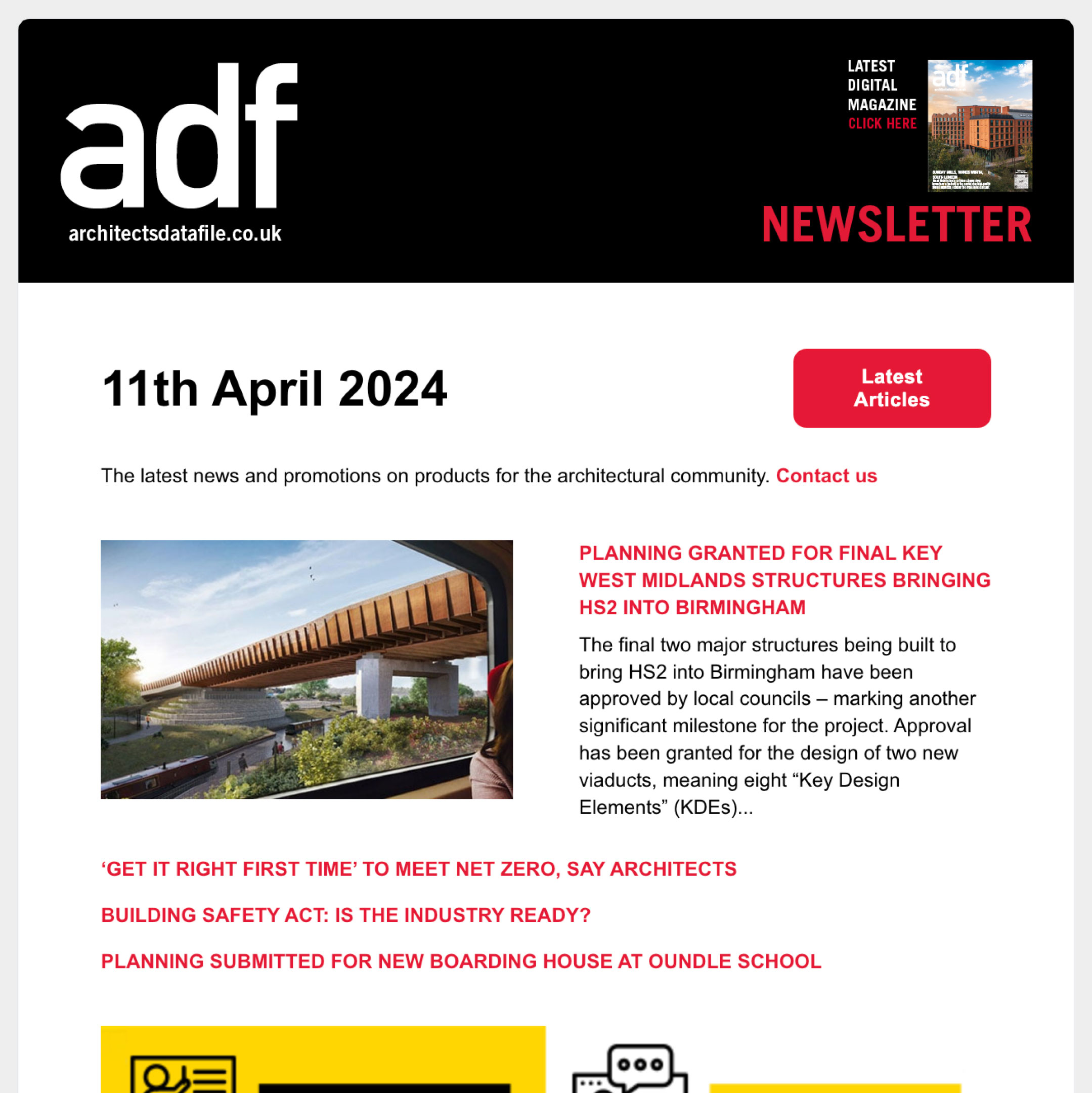

A high level of PMV would be about 75-80 per cent for a fully volumetric (Cat 1) building. But good levels of PMV can be achieved with the other categories. Hawkins\Brown’s 524-unit build to rent scheme at Plot N06, East Village in Stratford (split across two towers of 26 and 31 stories), uses a variety of systems (not including Cat 1) and is achieving around 70 per cent PMV.

Plot N06 uses an innovative system brought over from Australia that combines prefabricated floor slabs with curtain walling and this, along with a precast structure, bathroom pods, pre-fabricated service risers, pre-fabricated internal wall systems as well as other offsite methods has taken months off the programme.

Contractor Mace’s High Rise Solutions system used on the project employs parametric modelling tools and artificial intelligence to construct buildings, safer, faster and to a consistent high level of quality. It draws from a catalogue of components to design and manufacture the structure and facade sub-assemblies offsite, which converts site activities to an assembly process by installing modules concurrently with bathroom pods, utility cupboards and MEP service modules.

The process drastically reduces programme and improves productivity by up to six times compared to current industry performance. The construction programme has been reduced by 18 weeks with 20 per cent fewer workers onsite compared to a traditional building approach.

With the impending demographic skills shortage, not to mention the impact of Brexit, the construction industry needs to find ways of reducing its reliance on labour. MMC, aligned with digital tools and a more collaborative process, will provide this.

Standardisation

Closely aligned to a manufacturing-led approach is standardisation, which can both improve productivity and free up designers to focus on the areas they can bring greater value, like placemaking and improved functionality. There has been disquiet voiced by some architects regarding the aesthetic challenges modular construction can bring, but this should not be a barrier to good design, providing it is considered at an early stage.

It is critical that architects get involved in the current conversation about offsite rather than protesting a perceived loss of design freedom. This requires a proper understanding of the process of designing for offsite and the opportunities it presents. If the use of MMC is to be sustained it must be introduced at an early stage in architects’ careers and as such needs to be addressed during their education.

One way to address these issues is for architecture courses to teach the fundamentals of offsite design and manufacturing. This would include the Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) approach set out in the RIBA’s DfMA Plan of Work Overlay (which is currently being updated for publication in mid 2021), followed up with integration into the students’ design projects. This would be aligned with more detailed learning on the MMC categories and how to assess which would be appropriate for a particular site and project brief, and might also include an understanding of market capabilities, enough to undertake a light-touch optioneering assessment at the start of the design process (RIBA Stage 2).

It would ideally be accompanied by a closer relationship with industry, specifically with manufacturers, as well as consultants. This does however require a change in mindset. Designers need to integrate the method of construction at the start of the design process, not merely after planning approval. In the real world there are procurement barriers to this approach, but as a design philosophy it is an important starting point. Designers need to understand these procurement barriers – particularly with Design & Build – and be armed with the knowledge of how to persuade clients of the benefits of a DfMA approach.

Architects are key to initiating change through their involvement at the start of the design process, and their education needs to address the transformation required to make this sustainable in the long term.

Collaboration

It is essential that the construction industry improves productivity and achieves a step-change in procurement processes and approach to design. This will require collaboration between architects, engineers and manufacturers and better understanding of the manufacturing process by architects and their clients. It will also require recognition of the importance of design quality and placemaking by manufacturers.

Construction needs to learn from manufacturing, and it is time for change.

Nigel Ostime is a partner at Hawkins\Brown