A new home in a secluded corner of Hampshire combines a highly contemporary form with traditional vernacular touches. James Parker speaks to one of the two architectural practices involved who managed to provide a design that worked for client and planners

Nestled in a secluded valley in the South Downs National Park is a strikingly modern house, whose contemporary design displays vernacular touches such as brick cladding, but also remains something of a coup for its designers. Planning permissions are rare in such a setting, however despite its crisp, rectilinear looks, the building made it through on appeal.

Located just north of the village of Upham, near Winchester, Woodcote House replaces a series of brick buildings that had fallen into disrepair, including Herdsman’s Cottage, the original dwelling. Work started in 2017 on a new four- bedroomed house, designed up to RIBA Stage 3 by Winchester practice Design Engine, with the completed design delivered by Paul Cashin Architects.

Together with the small cottage, a garage and barn were demolished to make way for the new house, its footprint covering the combined square metrage of the buildings it replaces. The planning permission that got through at appeal also included a basement, which would have no visual impact, however this was not built in the end, as it wasn’t needed by the clients.

The couple, involved in the agricultural heavy plant business, already owned the site and buildings, which sit “in the middle of nowhere,” says delivery architect Paul Cashin.

The derelict state of the existing buildings meant that it would not be cost effective to refurbish them. However, the push to create a low-profile but substantial, monolithic modern home – one which would fully exploit the great views – was driven by the architects.

The clients contacted Design Engine, a well-known practice locally, having seen director Richard Rose-Casemore give a lecture, and asked him if the firm would be interested in taking on the project. However, with the firm normally specialising in larger schemes particularly in the education sector, and substantial overheads, they decided to offer it to former Design Engine architect Paul Cashin, who had formed his practice in 2012, to deliver the precisely detailed design. “I have a good relationship with them, we have collaborated on a number of projects,” he tells ADF.

Avoiding the main contractor route in favour of a local builder and other subcontractors proved to be a bonus, with the building firm (Wickham-based Baker Newman) producing the goods in terms of attention to detail for a high-end finish. Cashin knew of them after they refurbished a townhouse for a friend, and thought “if this couple is willing to put their faith in a young architect maybe they’ll do the same with the builders.” He is full of praise for their work, also that they were “really flexible about the costs, and the programme.”

The original plan was for the builders to tackle the envelope, however after introducing them to the owners, “they ended up doing the whole project and did a great job.” They did it “on a kind of construction management, informal basis; a labour plus materials approach, and open book,” says Cashin.

Having designed a dramatically modern brick and glass structure however, the task was to get it through planning, which was not to be underestimated. Planning was refused at the first time of asking – “you just don’t get to do that in the South Downs,” says Cashin. It was won on appeal with the help of a planning consultant, who made the argument that it was not a brand new dwelling but a replacement. This 250 m2 replacement would be around 250 per cent bigger than its predecessor on the site, with the council’s nominal limit being around a 35 per cent increase, says Cashin.

A further argument was made that helped tip the balance, namely that the footprint rule was based around creating ‘affordable’ dwellings in the region, but “no-one was going to be able to claim this was affordable housing stock,” says Cashin, “so the policy was void.” He counsels: “You don’t argue against the policy, you argue with the reasons behind it. If you can do that, the inspector has a bit more subjective awareness.”

Form

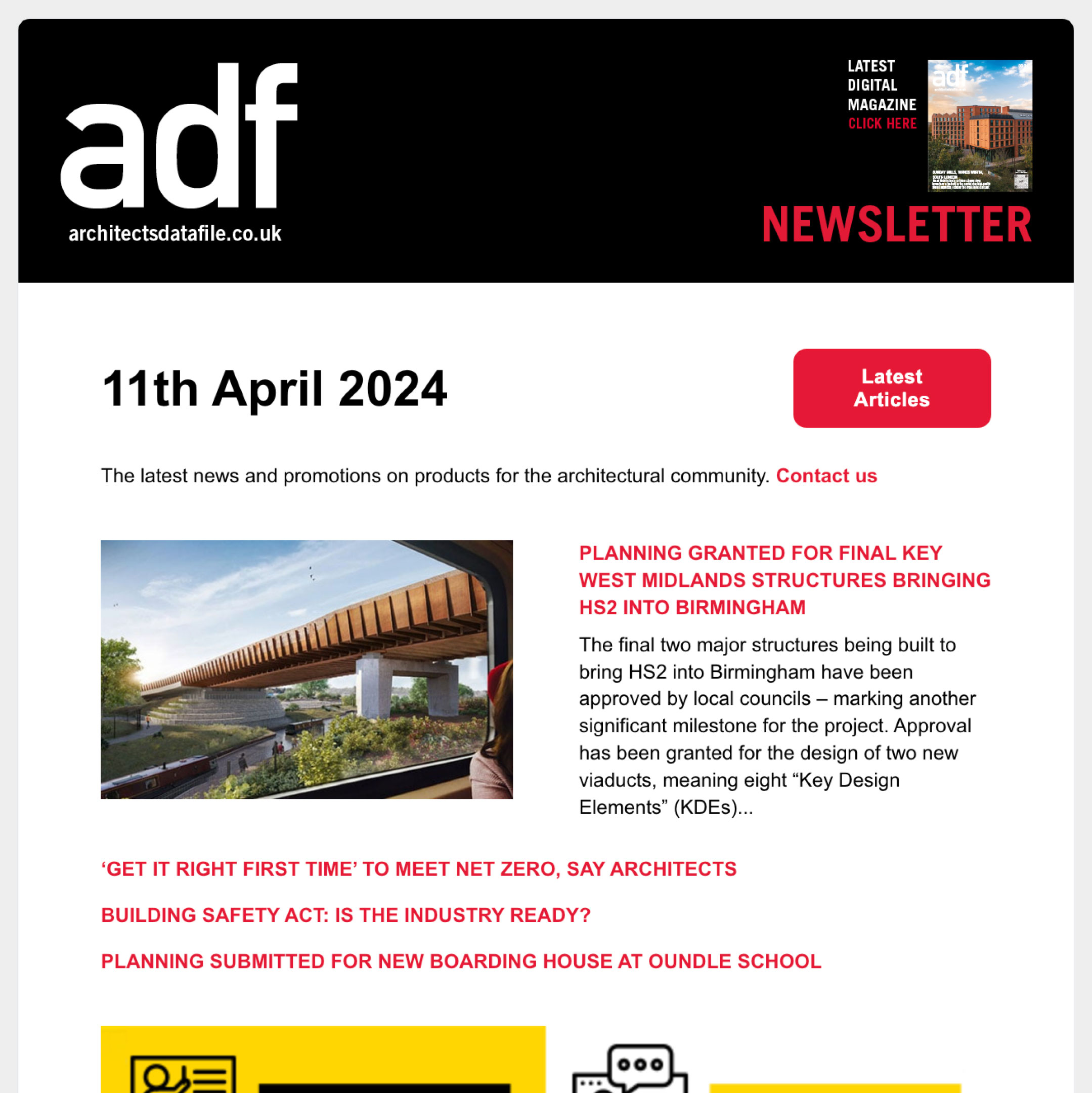

Inspired by contemporary European houses, such as in Switzerland, Holland and Belgium, the architects set about creating a striking, minimalist form that would also hunker down in this gently ascending hillside site, with trees sitting behind it. Replacing the barn and double garage would be a “low-profile single storey element which tries to bury itself in the hill a bit,” says Cashin.

Attached to this, there is a two-storey volume which stands where the demolished cottage was. From a distance, the silhouette would be similar to that of the former Herdsman Cottage as a result. However, the house departs from tradition in many respects, particularly its flat-roofed boxy profile, forming a somewhat unexpected contrast with the brick elevations.

The monolithic nature of the resulting composition was fully intentional, presenting an abstract, “sculptural” overall look, says Cashin, the building being viewable from all sides due to its isolated location. The long, “low slung” rectangular ground floor is terminated by the cuboidal block housing the bedrooms, which cantilevers to the north side. In addition, “openings are carved” out of it, adding to the sculptural effect, particularly the rectangular oriel window that sits at the top of the stairwell framed like the other apertures by very slim, dark aluminium. Cashin says that looking at the work of Belgian architect Vincent Van Duysen helped “give a steer on how to get the finer details right,” and the precise framing of the brick elevations using the specially fabricated aluminium copings shows the fruits of this attention to detail.

The low-rise section of the building, which sits further down the hill and is accessed externally by short flights of steps to north and south, largely comprises a loggia which encloses the open kitchen/dining/living space. The glazed door folds back to open four central panes – two are fixed at the edge – allowing access to a sheltered patio and outdoor dining area adjacent to the entrance on the south side, and a large lawned area to the north. In total there’s around a 7.5 metre possible aperture on either side.

Despite the apparently very formal nature of the plan, “nothing is symmetrical apart from the loggia window,” says Cashin.

Materials & engineering

While the focus was on creating a dynamic, modern family home, at the same time, says Cashin, “we were always conscious of trying to bring the old house into the new.” Therefore, brick was the obvious choice for the exterior, with the geology of Hampshire being of chalk and clay, and a Michelmersh Freshfield Lane rustic brick was chosen for virtually the entire cladding, bar a couple of aluminium panels.

However fitting with the designers’ aim of “looking to the past to help inform contemporary design,” the joints were raked out by 10 mm to offer greater relief to the walls – “much more depth and variety,” says Cashin. He adds: “We always think of every detail, even at the very beginning of a project.”

The structural engineer specified a steel truss frame, due to the need for a cantilever, and some large spans (up to 11 metres). The walls are brick, but some brick slips were used, such as for soffits. The cavities are extra-wide at 250 mm, hiding all the guttering within them to avoid impeding the exterior aesthetic, as well as housing copious insulation to counteract the large amounts of glazing.

The building has been designed to meet Code 4 of the Code for Sustainable Homes, with nighttime purge ventilation thanks to the 8 metre high stairwell to an openable roof light and a tilt/turn window to the north side of the ground floor, providing a chimney effect. Water is supplied from a borehole and aquifer.

Internal arrangement

With great views to the north and west, glazing was maximised in this project, particularly for the living areas on the ground floor. The spaces here are organised in a simple, linear way around a central corridor that’s open to the living space and which forms a spine leading from the front door at one end to the stairs at the other.

There is an uncovered car port to the west of the house, which, says Cashin, “could be converted to a further reception room later on.”

Interiors

The open plan layout “supports modern living,” say Design Engine Architects, but it can also be “conceived of as a series of distinct zones.” Ascending the stairs, the rooms “increase in intimacy and privacy,” culminating in the first-floor master suite.

The ground floor is split level due to the gradient, and up just a few steps of the staircase are the two ground floor ensuite bedrooms (one of which is currently being used as a home office). The staircase leads up the oriel window which has a view to the east, and two bedrooms with ensuites on the first floor. The split level helps add to the feeling of privacy, with the lower staircase marking a boundary between living and sleeping.

The property has bespoke joinery such as for the fireplace and bathrooms, and curtains, on silent tracks by Silent Gliss. Despite the fact that the property is not overlooked, the owners wanted some ability to control their interiors, and moderate heat loss. They also offer security benefits, says Cashin, “they can shut the whole house down when they are away travelling which they do a lot.” He is a firm advocate of bespoke curtains over blinds, as they are “much more luxurious,” and believes they are “coming back” as an option for contemporary properties. “Interior designers often like them, they keep reverberant sound down, stop heat escaping and wind coming in, and they can be quite pleasant to look at or hidden away in a pocket.”

The glazing to the bathrooms is breathtaking in that it is completely clear, and floor to ceiling in the case of the master ensuite. Cashin: “Technically, it should be obscured, but there’s no one to look in!” There is the concession of some brise soleil to shield occupants of the freestanding bath from the road to the north west, otherwise there’s an uninterrupted view of the landscape.

The precise details to the interior are perhaps most visible in the timber- treaded staircase, which has a recessed handrail plus a shadow gap, providing an unspoilt minimalist view up and down, and avoiding snagging clothes. There are no architraves around the full height doors, but shadow gaps instead. There is space between each riser and the treads are illuminated with soft LEDs to provide a low light to the space. “It took a lot of time to get right, and a lot of conversations with the builder, but they did a great job.”

The colours of the interior are a “yellowish white” which the client preferred, and which the architects were “slightly worried about,” but now “really like.” The ceilings are level throughout the spaces, so there are sharp lines, which the colour softens. The clients have provided their own, slightly quirky furniture, acquired from their global travels.

Conclusion

As well as achieving a decidedly modern building in an unspoilt rural landscape, the project is notable due to the trust placed in the architects by the client to have free rein, and the level of commitment to quality which repaid this trust. “If you had a client that was in any way controlling I don’t think it’d be anywhere near as good.” Cashin adds: “It was good they knew they didn’t know anything, them being honest about it was a real strength.”

The collaboration between client, architect and contractor was “very open,” says Paul, “everyone worked in a very candid way. Projects can break down if people don’t trust each other.

Part of the reason Paul Cashin was very thankful for the mutual trust which characterised this project was that it was a very early one for his practice, and he had little track record with which to convince the clients. “I didn’t have any work to show them when we were appointed, everything else we had done hadn’t been at that level. So we had to rise to the challenge, and we just got stuck in.”

Project FactFile

Architects: Design Engine (Stages 1-3)

Delivery architect: Paul Cashin Architects (Stages 3-5)

Contractor: Baker Newman Building

Structural engineer: Gyoury Self

Landscape designer: Andy McIndoe

Building control/Code 4 assessors: Butler and Young

Lighting designer: Intelligent Lighting Solutions