To celebrate the family firm’s 75th anniversary, ADF contributor Jack Wooler talks to Giles de Lotbiniere, Chairman of block manufacturer Lignacite, about the company’s foundation, and what makes it special

In 1947, retired ex-serviceman and engineer, Sir Edmond de Lotbiniere, was approached by an inventor – who had produced a new mix design for concrete blocks.

This was an attractive prospect – being just a few years after the war, there was a great shortage of building materials, and a clear desire to rebuild damaged sites across the country.

As such, together they began a journey that would continue through Sir Edmond’s family to this very day.

Producing blocks from the inventor’s formula in Brandon, Suffolk, where Sir Edmond was living, the beginnings of Lignacite were born. Soon, Sir Edmond had recruited his old sergeant from his regiment, who became Lignacite’s first works manager, and the company bloomed rapidly.

Ever-expanding from these humble beginnings, Lignacite has since grown over its 75 years into the acclaimed manufacturer it is today – with its blocks having been used in prestigious projects across the country – all while retaining its family ties, with Sir Edmond’s own Grandson, Giles, standing as the company’s chairman today.

“Surviving for 75 years is a noteworthy achievement and one we are incredibly proud of,” says Giles, commemorating the event.

“Lignacite has always stood for a high-quality product backed up by very good customer service, and as a company, we have always had a genuine desire to supply the best product that we can to our customers – and that’s a standard we continue to set for ourselves each and every day.”

The magic ingredient

Going back to the company’s inception, at first, the inventor’s original formula for Lignacite’s blocks included wood, sand, cement, and an expensive admixture.

Continuing the story from here, Giles says that, “when one day, the team ran out of this admixture, my grandfather said ‘never mind, let’s continue making the blocks anyway.’”

“To their surprise,” he continues, “they turned out equally well – in fact, even a little better – without the admixture.”

As it turned out, the “magic ingredient” was wood, which he tells me makes the blocks light, warm, smooth, and good in a fire.

As such, the company actually takes its name from ‘Lignum,’ which is the Latin word for wood, and to this day, the company continues to make Lignacite blocks with the same mix design.

To further explain the benefits here, “something quite fun,” says Giles, “is the sales technique used by my grandfather.”

“He would take a Lignacite block to a trade show with a wooden hand saw and a hammer and nail – he would then cut the block in two with the handsaw, and then knock a nail into one half, showing the versatility of the block, and just how easy it was to build with.”

“There are very few blocks that you can take a handsaw to and cut in half,” he continues, “if you are putting in electric cables or anything like that into a wall, being able to cut or chase into a block is a very valuable feature.”

Being part of what makes Lignacite unique, Giles believes that nobody else puts wood into blocks. This, he argues, is because it is a relatively expensive aggregate – the sugars in the wood decelerate the setting of the cement, meaning you have to put more cement into the blocks.

The expense is more than worth it though, he argues: “A normal, dense, aggregate concrete block will heat up to a certain degree and then shatter. Whereas, if you have wood in a block, it won’t burn because it’s locked up in the matrix of the block and the oxygen can’t get to it. Instead, it calcifies and goes black and hard. As a result, Lignacite blocks have a very good fire rating.”

Besides this, in more recent times, he tells me that blocks containing wood have also been recognised for having the attribute of locking up CO2: “Because trees absorb CO2 for photosynthesis, which is an essential process for all plant growth, it means that putting wood into blocks locks up that CO2 permanently.”

The proof is in the projects

This winning formula has been a clear success, not least evident in the wide range of revered projects the blocks have been installed in across the country.

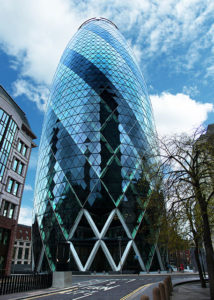

When listing these to me, two of the major projects that immediately stand out are The Gherkin and The Shard, which, as Giles says, “are not only iconic British buildings, but iconic buildings worldwide.”

The Shard, for example, was built using 140,000 Lignacite blocks, each containing over 50% recycled material. These were used to construct the four basement levels, providing a substantial platform for Western Europe’s tallest building. To construct The Gherkin, 10,000 m² or 100,000 blocks of Lignacite were used in the central core.

“Those we supplied for the Olympics were also some of the most prestigious and fun,” says Giles. “We were involved with six projects altogether. Those were the Olympic Stadium, Velodrome, Athletes’ Village, Orbit Tower, Westfield Stratford City shopping centre, and the Handball Arena.”

“We’re also proud of the many innovative AFM projects we have been involved with and the ongoing product development that we have conducted throughout the years. We have led the

way in using glass and recycled materials in masonry.”

He continues: “We’ve also had some really fun projects like The Wedding Chapel in Blackpool, which was designed by dRMM and constructed from blocks containing blue luminescent glass in a matrix of limestone. They were then polished and cut into Roman brick, which was staggered and built to look like the prow of a ship.”

“The glass warms up during the day and then gives off a luminescent glow at night, making the whole building glow – it was a really spectacular project that caught a lot of people’s imaginations within the industry and beyond.”

Ecological innovation

Despite achieving a record turnover in 2021, with customers keen to reach for a trusted and proven product during uncertain times, Lignacite is not resting on its laurels, and hopes to be ahead of the crowd where it matters – focusing especially on the company’s ecological innovation.

While the Government is now mandating an industry-wide net zero target for 2050, with interim measures, Giles tells me that Lignacite had already committed to its own, earlier target of reaching net zero by 2030.

“We have been working towards this goal for a number of years,” he explains. “We already put a lot of recycled and renewable aggregates into our products and not much energy is required to produce concrete blocks.”

He tells me that blocks have a “very low embodied energy,” which he explains is in part because they cure largely without any additional heat or energy requirements.

“A brick needs to be fired in a kiln, whereas our kilns get up to about 40°C just through the exothermic process of cement going off,” he says. “So, as long as you start with your temperature at 2 or 3°C and you fill up a kiln with uncured concrete blocks, the temperature will get up to 40°C and they cook themselves. They therefore have half the embodied energy of a brick, and a fraction of the embodied energy of steel.”

“We also have our own borehole at Brandon and recycle all of that water, using it within our manufacturing process.”

Further to that, the company is already generating “a fair proportion” of its electricity through solar panels, Lignacite recently implemented an app-based electronic proof of delivery (EPOD) system and is “continually” trying to find other recyclable materials for its products.

An “innovative and amusing” example he gives me of the latter was during the construction of the Athletes’ Accommodation in the Olympic Village, with the client requesting green glass in a particular block.

“It was difficult to get hold of the green glass, so we got everybody to drink lots of wine and bring the bottles in,” he says.

“We then ran over them with a roller, crunched up the glass, put it into the blocks, and started to supply them, only to find out that they didn’t want the green glass and it had to be brown! So, we then had to drink lots of beer and bring the bottles in. The eventual project, sure enough, involved brown glass!”

Roots and branches

Now looking to the future, Giles is excited that, in 2023, the company will be fully operational at its new Brandon plant, which is currently in development. He says this will lead to even greater efficiencies and consistencies than ever before.

“I hope in the next few years we may have secured permission to develop our site at Nazeing and be able to expand that,” he says.

“We certainly should be a way down the road of having found another source of aggregate or have invested in securing our own aggregate supply.”

On the company’s continued role in construction in the future, amidst a rapidly changing landscape, Giles feels strongly that, “while new building designs and concepts come and go – whether it’s timber frame or offsite construction – in the 30 years that I’ve been involved in the industry, bricks and blocks have survived, and continue to be a very cost-effective and versatile method of construction.”

“I’m confident that in 10 years’ time that will be unchanged – so long as we keep innovating and keep using a high proportion of recycled materials, we can go on producing a very good and sustainable product that people want and need.”