Following June’s significant changes to Part L, Nordan’s Sonia Travis reviews the implications for window specification, and aluminium-clad timber in particular

The state-of-the-art demonstration COP26 Zero-Carbon House at last year’s international COP26 climate conference in Glasgow was an effort to highlight the importance of building fabric choices in achieving net zero.

Less than 12 months on from COP26, and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) has shown its teeth and commitment to reducing building related carbon, by introducing new Building Regulations.

The new Part L has of course been years in the making, and is something of an interlude for the industry prior to the advent of the Future Homes Standard in 2025, the full industry consultation which begins next year.

The new regulations aim to reduce carbon emissions from new build homes by 31%, and all other new buildings by 27%, and operate on a building-by-building basis, as opposed to whole sites. The ultimate objective is to reduce total building carbon emissions by a minimum of 75% by 2030, in order to meet wider legally binding net zero commitments.

All these changes will of course impact on the U-values of any and all building fabric, and have significant implications for windows.

The Future Buildings Standard policy document has already been published, and sets out new Building Regulations and the proposed changes to Part L (Conservation of Fuel and Power), and Part F (Building Ventilation) – as well as new requirements to address the risk of overheating in new residential buildings (Part O).

The changes to Part L cover both new and existing dwellings, with Part L1A laying out new energy efficiency standards for new build homes. Part L1B covers renovations and extensions to existing homes, and recognises that it is not always feasible to meet new build standards, however replacement thermal elements, such as roofs, walls or floors must meet the Part L1A standards.

In June, the maximum allowable figure for windows was lowered from 1.6 W/m2K to 1.2 W/m2K, and will shift further to 0.8 W/m2K in 2025. Heat is lost through a window’s glazing and frames, so both must be factored in when calculating a window’s U-value.

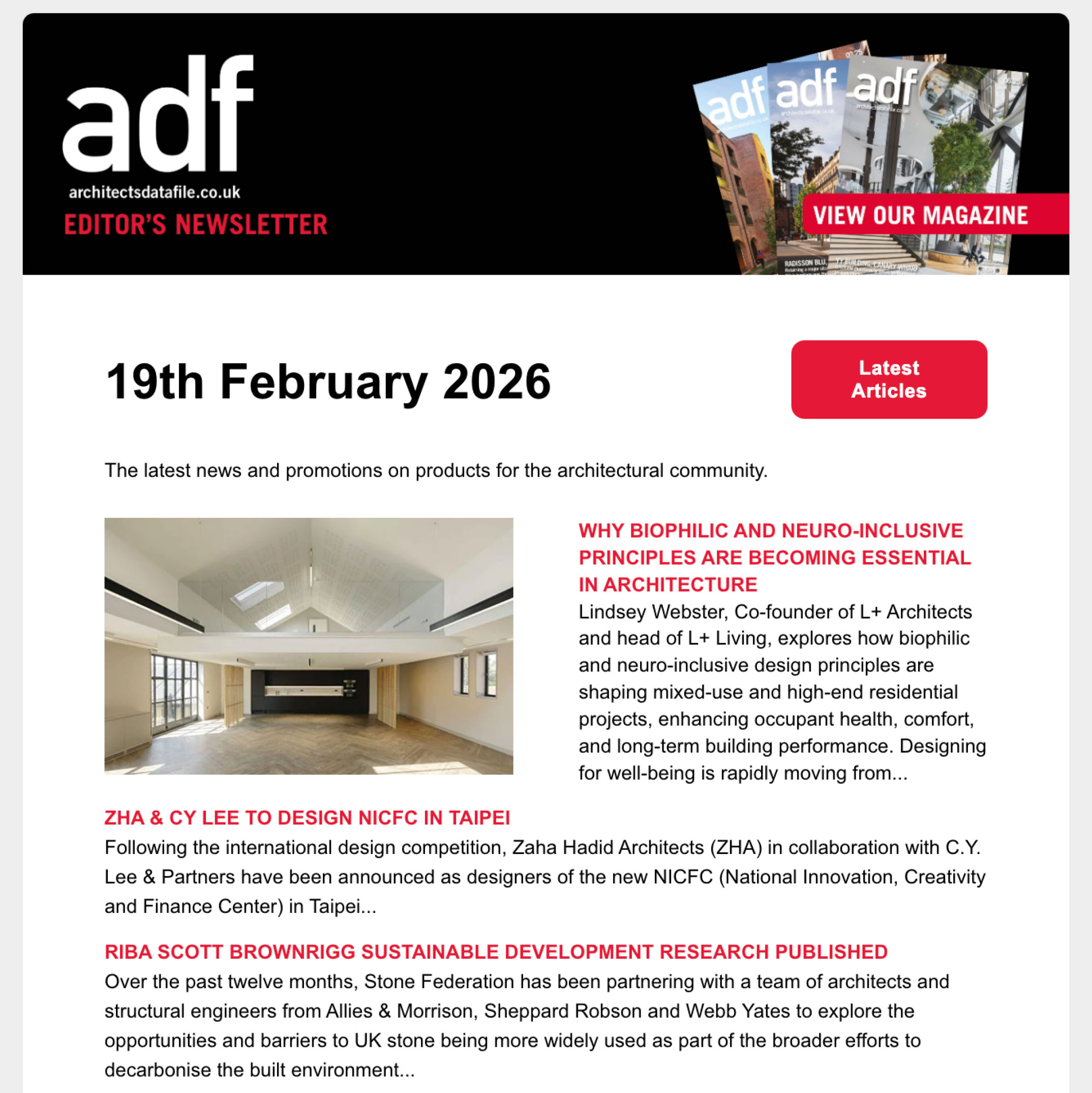

As you would expect, double and triple glazing gives you a lower U-value and better insulation, but the type of frame material chosen has a bigger impact than is sometimes anticipated. For example, an aluminium-clad timber window frame can achieve a U-value of 1.2, while a typical PVCu, aluminium or composite window frame would need to be triple glazed to achieve that figure.

When combined with triple glazing, aluminium-clad timber frames can hit U-values as low as 0.74, due to the natural insulation qualities that timber develops as it grows, and the millions of tiny air pockets in wood’s cellular structure.

Although architects have long known the benefits of timber, it appears that Part L has given timber frame windows something of a leg-up in the pecking order of building materials, nullifying the increased capital cost, and making the benefits more financially accessible.

The impact of Part L can already be seen in the fenestration industry, with window manufacturers reviewing the design and price point of their products based on the materials used.

It would be a step too far to suggest that this was the exact intention of those who framed Part L, but it’s certainly a good practical example of how these changes will drive change, lower carbon and increase quality.

There are numerous projects over the past 30 years where architects have specified high-performance timber framed windows that far outstripped Building Regulations at the time, only for standards to then subsequently advance. Castle Court is one such example, a high-rise social housing development managed by The Guinness Partnership. It was regenerated over 30 years ago, but will still meet the Future Homes Standard in 2025.

Switching to better quality window frames will also have positive benefits for the whole life carbon impact of a building. Less glazing and longer product life spans reduce the release of embodied carbon (the emissions generated from material abstraction and manufacture), due to the reduced use of materials, maintenance and replacement.

On top of this, timber is also a natural carbon sink, absorbing carbon as it grows, and is therefore carbon negative at the point of harvest and manufacture.

In conclusion, if architects require assistance in calculating the whole life carbon value of a building material, then they should look out for independently verified Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), or their equivalent. We now have EPDs in place for the vast majority of our product range, meaning a transparent, third party audit of all embodied and operational carbon.

Sonia Travis is commercial sales manager for the North of England at NorDan UK