Bob Wills, director at Medical Architecture, explores the movement to design health facilities with a focus on individuals and not illnesses, and with less reliance on acute hospitals and more focus on integrated community facilities for holistic wellbeing

Published in February this year, a new report by The King’s Fund offers a fresh perspective on a challenge that the NHS has faced for many years. It recalls that, “since at least 1974, and arguably earlier, successive governments have aimed to make the health and care system less hospital-focused and more focused on primary and community care.”

It cites the World Health Organisation and its view that this approach is the most inclusive, effective, and efficient way to enhance people’s physical and mental health and wellbeing. This is about “improving both the experience and the quality of care that people receive, while boosting prevention or, at the very least, reducing the speed of onset of disease,” says the King’s Fund. “It is also about meeting people’s needs and making sure each part of the health and care system is freed up to provide the care it is best placed to offer.”

Many of us will recognise this as a proactive, preventative approach to health, as opposed to a reactive, treatment-based approach, with care delivered closer to people’s homes.

Shifting the focus to community health

Despite this long held ambition, the report highlights a mismatch in action, with the proportion of Department of Health and Social Care spending on primary care falling in recent years from 8.9% in 2015-16 to 8.1% in 2021-22. Similarly, while the NHS has received additional funding in recent years, acute hospital trusts have seen 27% funding growth since 2016-17, compared to community trusts who have experienced just half that level of growth, at 14%.

The King’s Fund report goes on to suggest reasons for the lack of change, before setting out a solution for refocusing of the health and care system, which is detailed and far reaching, covering policy, leadership, funding, and workforce.

A critical element to this is cultural change: “The increasing complexity of people’s health and care needs requires an integrated, holistic response, rather than a ‘body part’ or single condition response. There needs to be more of a focus on people and outcomes, rather than processes and outputs.” In terms of our approach to healthcare facility design, this is an important shift in thinking, and one that we have seen embraced in pioneering community health schemes in recent years.

Person-focused care

One example where this approach has proven to be successful is The Jean Bishop Integrated Care Centre (JBICC) in Hull. Prior to the project commencing, Hull and North Yorkshire Integrated Care Board faced numerous challenges. Hull had around 25,000 residents living with frailty, and 3,200 with severe frailty. As a result, the health system was overwhelmed with non-elective hospital admissions, struggling to find beds for elderly patients amidst peak admissions and growing demands from the ageing population. A 2012 study found that a third of older patients admitted to hospital in emergency had no clinical need to be in a hospital bed, and that admission quickly reduced the ability for vital rehabilitation and ‘reablement.’

In response, and informed by engagement with residents, Humber and North Yorkshire ICS developed an ‘anticipatory care’ model that completely redesigned the approach – creating an out-of-hospital service to help people to stay at home and out of hospital. We were commissioned to work with stakeholders to develop the first facility which could deliver the care model effectively.

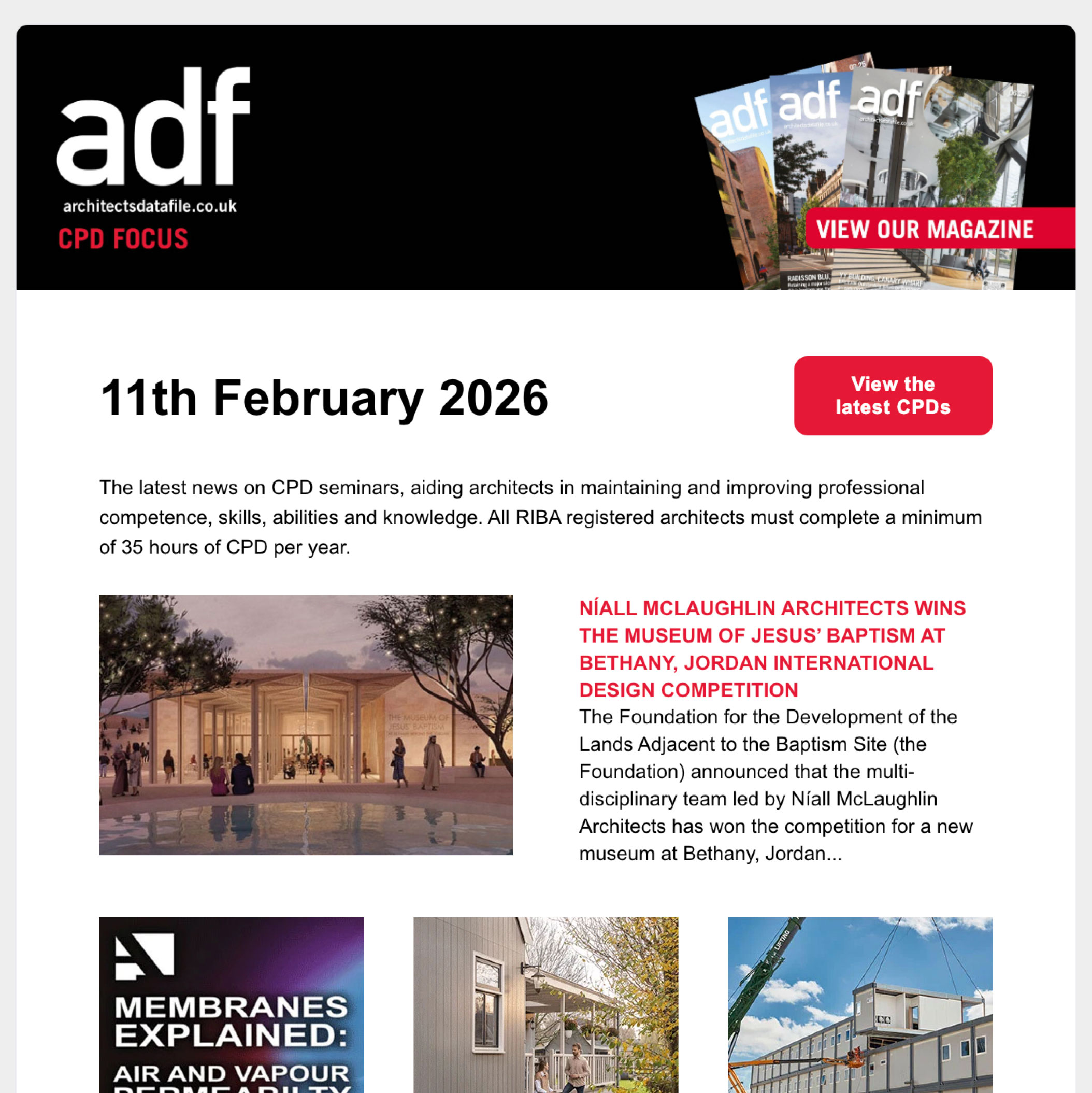

Adopting an entirely new way of delivering health services, the centre brings together a range of specialist services to provide a more holistic approach to health, care, and social support. Unlike regular community health facilities, where patients receive assessment and treatment for a single health complaint or condition, at the JBICC patients receive a full physical and mental health check, as well as help with other social challenges. They may spend an entire day there, but they leave treated and with a care plan. The type of facilities offered reflect this extended visit and include a cafe run by Inspire Hull, a charity which aims to improve physical and mental wellbeing, through the development of friendships and feelings of purpose. Activities are curated which bring people together to tackle feelings of social isolation.

The therapeutic and non-institutional character of the design with views to gardens and landscape from many areas of the building, create a comfortable environment to support patients during these extended visits.

Relieving the strain on overstretched acute hospitals

A recent study, led by researchers from the Wolfson Palliative Care Research Centre at the University of Hull, assessed the wellbeing of patients who received this more holistic person-focused assessment at the centre compared to those who did not. It showed, for those living in their own home, a 15-20% reduction in emergency department (ED) visits and a 10-25% reduction in emergency admissions for the 12 months after their assessment compared to the 12 months prior. Also, for residents in care homes, there has been a 20-25% reduction in ED visits, and for the frail cohort who had more than five ED visits in the 12 months preceding their assessment, there is consistently over 50% reduction in ED visits and admissions in the following 12 months.

Clearly, then, long-term investment in the right kind of community-focused facilities can reduce demand for acute services and bring about savings to the wider healthcare system, as well as improving the wellbeing of individuals.

Sustainable evolution of the healthcare estate

The King’s Fund points to a need to invest in primary and community healthcare estates to promote joined-up, integrated working locally between public partners across health, social care, and community services. However, despite recent initiatives to bring forward innovation in the delivery of community health, investment remains weighted towards capital investment to acute services; the New Hospital Programme being a prominent example.

The Cavell Centre programme, named after Edith Cavell, a British nurse during World War I, is one such initiative that looks to the future. The programme began after Medical Architecture, with John Cooper Architects, proposed the development of a blueprint for the transformation of primary and community care facilities in England. Developed with NHS England and NHS Improvement (NHSE/I), the aim was to optimise and standardise the briefing, planning and design process to allow the business case process to be streamlined, increasing quality and reducing design costs at each project stage.

The proposed Cavell Centres that emerged pioneered an approach to standardised yet adaptable planning, with a specific approach to MMC, net zero carbon design, and high quality, wellbeing-focused environments. Following on from this work, we were commissioned alongside Passivhaus design specialists Architype to co-design one of six pilot schemes for the programme – the only one to be designed to Passivhaus standards.

Social prescribing as a route to health & wellbeing

Like The Jean Bishop Integrated Care Centre, the strategic vision for the Cavell Centres recognises that social factors in health are as significant as clinical factors, and therefore combines both models to proactively address the barriers to improved community health and wellbeing. This formed a central feature of the pilot scheme design.

Setting a new standard for community health facilities, the building hosts a varied health and wellbeing offering, including multiple GP practices, community diagnostics, therapy services, outpatient services, third sector social prescribing organisations, and a health-centred commercial offer. The building is designed to be highly flexible to allow this mix of services and tenants to adapt over time. Strong internal connections to quality external landscaping with lawns, planting, and water features; and inviting, non-institutional internal spaces; enable a variety of wellbeing activities. This, combined with access to local authority support, links patients with opportunities for social prescribing, integrating health and wellness into the community.

Competing priorities for limited funding

Currently, NHSE has paused the development of the project business cases to focus on developing the programme business case ahead of a bid for capital funding for the programme at upcoming spending reviews. We are hopeful that initiatives such as the Cavell Centre programme will be able to demonstrate the benefit of a long term investment in a preventative approach to healthcare, in relieving pressure on an already overstretched system.

In their report, The King’s Fund describes ‘hierarchies of care’ – urgent problems taking priority over longer-term issues – as a reason for underinvestment in community healthcare. For

example, treatments for urgent medical problems taking priority over services that prevent the development of problems.

It recommends that leaders need to be clear about why a change in focus is needed: “which is to deliver improved care and improved outcomes, and to ensure the health and care system is sustainable for the future, rather than to deliver cost savings in the short term.” Clearly, the challenges the health service faces are complex and multifaceted, and no quick solution exists, however successful pioneering projects like The Jean Bishop Integrated Care Centre, demonstrate the value of a person-focused, preventative approach, which the Cavell Centre programme is well placed to continue – if funded as a priority.

Bob Wills is director at Medical Architecture