All sectors are having to strike the tricky balance between addressing the climate crisis and navigating a pessimistic economic outlook. Thomas Pearson from Arup looks at an example of renovation and renewal in hospitality as one solution

The built environment is a key emitter of carbon and greenhouse gases, for example, hotels account for around 1% of all global carbon emissions. It’s now widely reported that 80% of the building stock we will be using in 2050 is already in existence, so the hospitality as well as the AEC (architecture, engineering and construction) industries must prioritise decarbonising the structures in situ.

Fortunately, the AEC industry is at the vanguard of innovation. As part of this, it needs to reflect on the best use – or rather reuse – of buildings, with renovation a key tool.

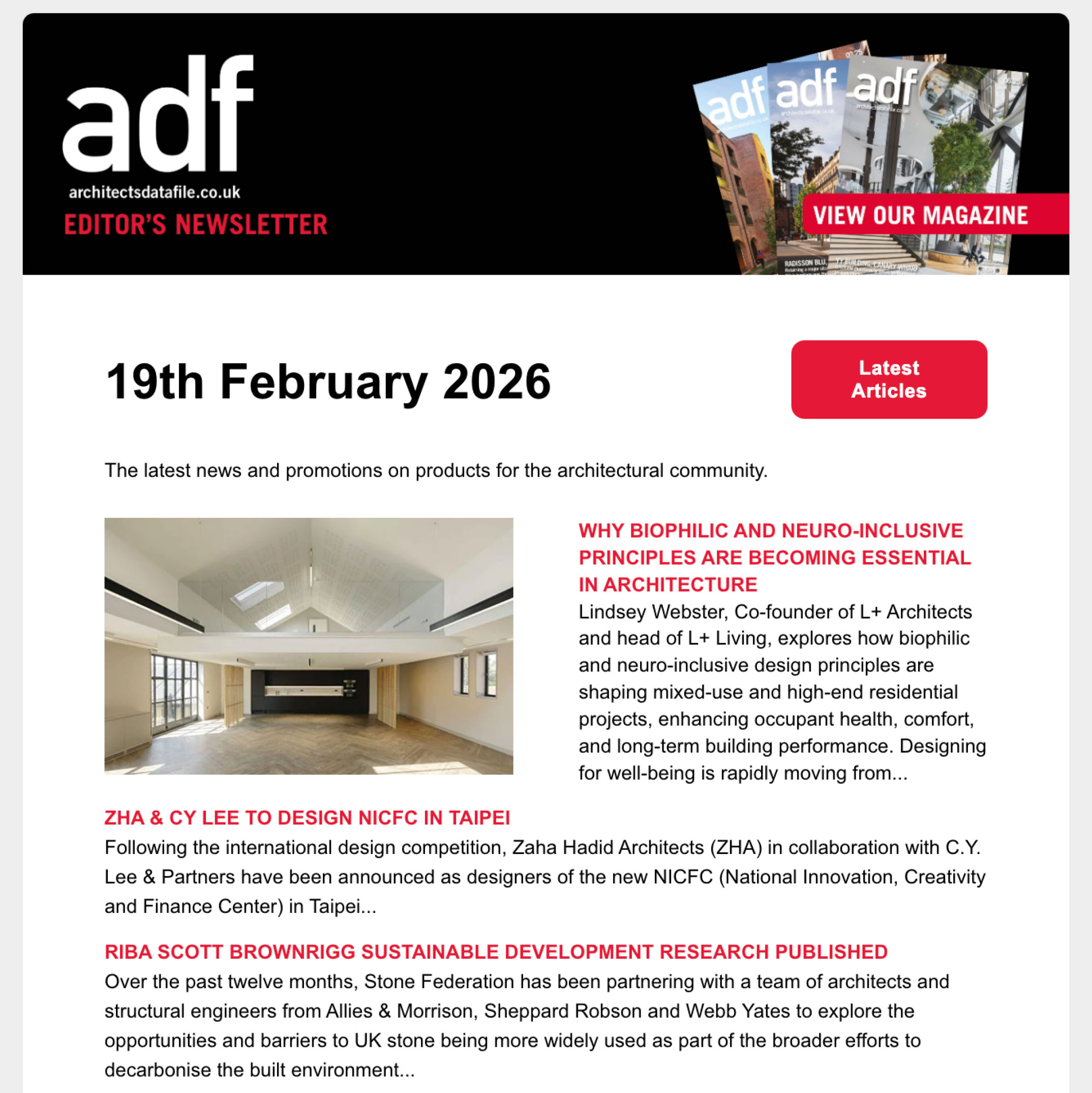

In Spring 2021, the Grade II listed Birmingham Grand Hotel reopened, nearly two decades since it last shut its doors. Originally built in the 1870s and one of the best surviving examples of Victorian architecture in the city, the hotel had fallen into a state of disrepair since ceasing trading in 2002. Despite this, the building was listed in 2004. Shortly after, problems with its stonework led to a crash-deck scaffold being assembled around the upper floors to catch falling debris.

In 2010, Arup was brought on board by Birmingham agent Hortons’ Estate to explore cost-effective options to stabilise and restore the facade stonework, which was hidden behind years of unsuitable repairs. Within our conservation architecture practice, we place particular importance on the original materials of a listed building. In this case, the decay was so widespread that repairing the Grand Hotel’s facade demanded technical innovation, design creativity and painstaking craftsmanship.

We were tasked with solving three key challenges to help repair and restore the hotel. This saved the building from demolition, which continues to stand tall as a landmark of Birmingham’s heritage, highlighting the key role of renovation in sustainable construction.

Solving hidden problems

Upon initial inspection, the facade’s masonry was found to be unstable and soft – so much so that, in some places, it could be torn by hand. A thick build-up of cement, paint, bitumen and resin had also trapped moisture within the stone behind, and masked its decay.

The original design brought with it further issues. These included incorrect weathering details that were absorbing rainwater rather than pushing it away. Furthermore, the materials were not suitable, with the stone itself of poor quality, meaning it was inappropriate for use in areas of heavy exposure.

This was clearly unsafe for human use. However, the necessary work of stripping away the coatings and stabilising the damaged stonework was set to significantly eat into the finished surface of the facade. This would have altered the carved details on the facade, creating a misshapen appearance. We needed to balance preserving the original look and feel of this landmark building, with the severity of the repairs needed.

In response, we developed a set of conservation principles to carve into the surviving stone, effectively re-setting the entire building envelope backwards. This helped to reinstate the original grandeur of the facade, without changing its outward aesthetic.

Recreating the finish

Renovation required the facade to keep its original finish and key identifying features. In tandem, we wanted to ensure the use of new materials was kept to a minimum to avoid waste, thus reducing the renovation’s environmental impact.

Solving this aspect of the challenge demanded detailed understanding and meticulous planning. Point-cloud surveys of the facade were therefore taken before and after the coatings were stripped. This allowed the team to specify where and how each individual flat area should be finished. This information was then translated into a set of small elevations for use by the masons on site, showing how far each block should be dressed back, to fit into the overall arrangement.

Decorative details were re-carved insitu, as far as possible, to recreate the entire ornate finish of the building, while in turn keeping the quantity of new stone to an absolute minimum.

Supporting local trades

For sustainability to have as broad an impact as possible, it cannot just focus on environmental effects. While this plays a vital role, the industry must also focus on the social outcomes.

The project supported businesses and craftspeople from the region, sourcing both labour and materials locally. This included stonemasons from Midland Conservation, who carried out repairs using traditional tools and techniques, working by hand to conserve almost every piece of decorative as well as most of the plain ashlar stone. This work led to Historic England describing the scale and traditional nature of the stone masonry repairs at the Grand Hotel as unique – in 2015 at least – for a non-ecclesiastical building.

Looking forward

Our structural engineers were subsequently involved in redesigning the internal structure too. This involved the construction of a new full height central circulation area and a steel structure for penthouse suites.

Overall, these repairs and renovations have reimagined and reinvigorated the Birmingham Grand Hotel for future generations to enjoy. This project perfectly exemplifies how the industry can have a positive impact on the environment – using local experts and materials, avoiding unnecessary waste and stabilising a heritage structure. As such, it serves as a template for others in the industry to make do and mend wherever possible.

Thomas Pearson is an associate at Arup