Architect Jane Burnside took on an unusually wide range of project roles to create her tranquil, contemporary home and workplace on the Isle of Mull, inspired by origami. Nik Hunter reports

Introducing a contemporary building into a traditional landscape such as on the Isle of Mull takes enormous amounts of respect, skill and forward planning.

Fortunately, award-winning architect Jane Burnside has the experience required.

Running her own practice, Jane has nearly 30 years’ experience under her belt, and has designed many contemporary homes. However, when she decided to not only design but also project manage, and act as foreman and interior designer for her own self build, she realised she needed an entirely new skill set.

Jane splits her time between her practice HQ in Ballymena in her native Northern Ireland, and her new home on Mull in which she shares with her architect husband, David Page. As well as being a co founder of Page\Park Architects in Glasgow, he’s also an artist.

A keen sailor from childhood, Jane’s sailing trips up the west coast of Scotland instilled a love of the island. In 2014, when the couple came across a two-storey, stone house for sale in the conservation area of Tobermory, they jumped at the chance to do their first project on Mull.

The property had already seen some renovation, as Jane recalls: “It had been split into two flats in the fifties, but the previous owners had managed to purchase both and restored it back to one property.”

The previous owner was a haulier and had built an enormous, two-storey steel shed in the back yard which presented Jane with further potential for redevelopment.

For five years, The Art House (as they named the old stone building), was the couple’s much-loved home, but in 2019 they turned it into a holiday let and moved into their new home after managing to realise the shed site’s full potential.

Aware that councils are usually keen to prioritise development on brownfield sites, Jane had always hoped that eventually she and David would be able to develop the old, two-storey steel haulage shed at the back. “We had a good idea that we’d be allowed something, we just didn’t know what, because we were in the conservation area – that was a real challenge.”

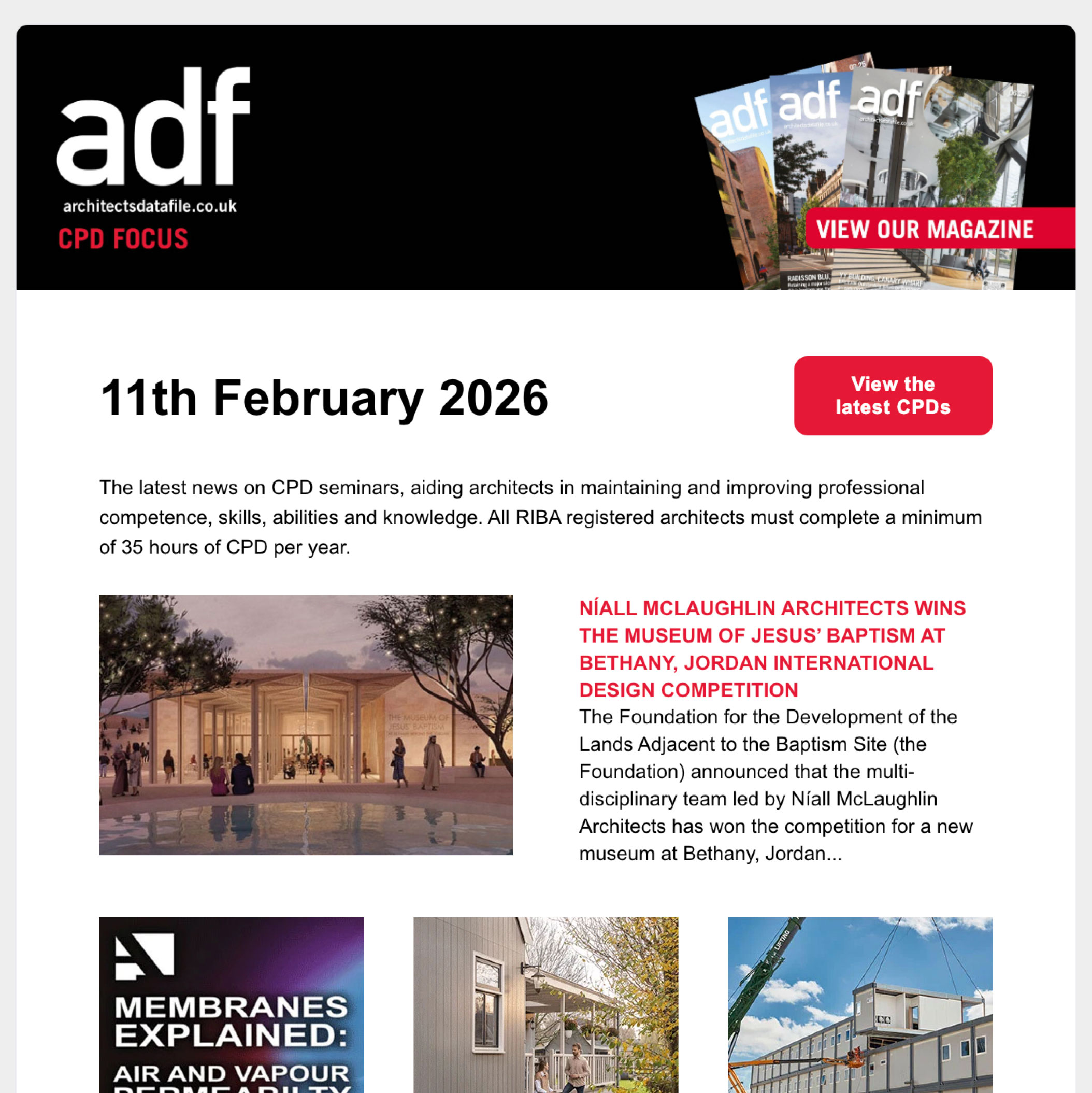

Having written a book about how to design contemporary houses in both landscape and conservation settings in 2013, ‘Contemporary Design Secrets,’ Jane followed her own advice when applying for planning permission to build the Origami Studio – a bold, contemporary, two storey home.

Persuading planners

She says that her book came in handy to help assuage the concerns of planning officers: “When you apply for permission in a conservation area, it’s not only the size and scale of the proposal, but also, what’s the design concept that will make it blend into the historic fabric.” Jane used her book as a reference: “I could point to the houses I had built, and demonstrate the level of detail I apply.” She continues: “ It’s one thing drawing a sketch for a planning application; it’s another demonstrating to the planners that you can deliver it. My book helped give the planners confidence.”

In terms of detail, she not only means materials that are locally sourced, but items like the mortared verges and heavy aluminium gutters would all be in keeping with existing properties in the area. “It’s these little details that tie a building into its historic setting even when the overall design is contemporary in nature.”

An important feature in her concept design was a large masonry gable facing onto the street, followed by two largely glazed gables stepping back from it.

This solid form mirrors the historic Art House alongside it, and cleverly conceals from view its two glazed counterparts.

Concentrating the glazing here allowed Jane to create the solidity where it mattered, and also tied into the vernacular.

“Tobermory has many buildings with big stone gables and tall chimneys. The Art House has them, and we wanted to reflect that in Origami Studio.” Another obvious solution to help the building blend in was to retain the walls of the old shed as a boundary wall. “We cut the walls into a stepped shape that broke down the mass of the existing walls.” This eliminated the issue of any overlooking, and afforded the neighbours their privacy. “The view from the street is very respectful; it’s only when you go past the solid gable that you see the glazed walls.”

Interiors

Internally, Jane’s aim was to create a layout that delivered what she and David required now, plus what they might also want 10 years in the future. Her solution was to put two guest bedrooms, her work studio and David’s art studio on the ground floor. Making David’s studio a ‘communal’ space that feeds into Jane’s studio and the two other bedrooms, offers the flexibility to turn her studio into an additional bedroom when required. “I like working with open plan design, as you can cut down on circulation space,” she says. “There are no corridors here, and no wasted space.”

Upstairs, Jane’s aim was to create a space akin to a large apartment which incorporates the main bedroom, an open plan living/dining/kitchen space and an outdoor balcony which all take in the view over the bay. “It’s simple – the roofscape defines the three spaces underneath so there’s a natural breaking up of the open plan into its different uses.”

At first glance the property presents an abundance of space and light, but this belies the fact that for Jane it was the most restrictive site she’s ever worked on.

“Building between The Art House and the boundary walls of the old shed meant that every millimetre counted, and that was a challenge because I knew exactly what I wanted to fit in.”

For Jane this meant that even at the sketch design stage, she was phoning scaffolding companies to check the sizes of scaffolding planks and stanchions to ensure they would fit onto the site. “As an architect this isn’t something you would normally do, but I needed the hard facts so I knew exactly what I had to work with.”

Following plans being submitted, permission was granted within six weeks.

Jane then began the construction drawings for Building Control and additionally began her project manager role, sourcing materials, preparing quantities and obtaining costings.

Mass appeal

To offset the amount of glazing and associated overheating in the building, Jane opted for heavyweight construction with double-skin blockwork walls instead of a timber frame. The glazed gables all face east towards the bay, and as a result, “we don’t have too much glazing facing south,” she says. In the dining area there are rooflights, but no wall apertures facing south; in the living space there’s a large south-facing glass wall, but a solid roof holding solar PVs.

With a heavy thermal mass in the concrete floors and walls, the high peaks and troughs of internal overheating and cooling are eliminated, instead the mass absorbs the excess heat during the day and releases it at night. She explains her ethos: “Timber frame buildings are classified as ‘lively,’ because they are very responsive to heat, and temperatures will spike; I find that very uncomfortable.” Jane continues: “I like the permanency of traditional masonry construction, which is particularly suited to wet climates in Scotland and Northern Ireland.”

Jane’s choice was an 80 mm steel frame hidden within the double-skin blockwork walls, and designed on a CNC machine.

Jane says: “It’s like a Meccano set; digital perfection. A very slim steel frame sets out the whole building.” Jane was able to erect this frame off the existing concrete slab of the steel shed. This meant no new foundations were required, just a few adjustments in the steel frame to ensure that each leg of the steel was slightly longer to account for the slope on the slab.

In actual building time, the project took six months but in ‘real time,’ 10 months.

Working with a small team of tradesmen, Jane took on a further role – site foreman.

The build was carried out in three two month stints. “The team would leave the island for two months and then back for another two and so on.”

For Jane it was the ideal solution, as it gave her time to plan the work, order materials and to keep her architect’s business going. “It also worked with drying out time. I’m an architect – I don’t usually worry about ordering materials or have to deal with shortages and delays – that’s usually someone else’s problem but in this instance, it was mine!”

Fortunately, there was only one real hold up. “We needed a specific weight of Spanish slate, and a particular setting out for the nail holes, as we’re in an area with high winds. They had to be specially ordered and took forever to come.”

The building also had to stand up to occasionally horizontal rain (when combined with 60 mph winds). After some research, Jane came across Illbruck tape which she likens to a strip of wetsuit material glued onto the window frame and masonry walls. “We’ve been here two years, and no leaks.”

Other problems that were posed by building on an island included things that Jane completely took for granted on the mainland, and she had to resort to manual labour. “Bringing a crane on to the island for a day to lift precast slabs would have been prohibitively expensive, and there was no concrete pump on the island either for the screed.” The solution was concrete T-beams and blocks for the first floor which had to be lifted by hand, and the screeds were mixed on site, lifted in buckets on a homemade pulley system and levelled by hand. This was a vital part of the construction, as the heavyweight floors were important “not only for thermal mass and sound proofing between floors, but their weight loaded onto the steel frame made the whole structure stronger.”

When the dirty work was finally complete, Jane’s transformation into an interior designer began. In the kitchen she chose a concrete effect for the doors to the island which she contrasted with black composite work surfaces. The concrete finish also complements the backdrop to the wood burning stove, a feature Jane designed with her builders. She took leftover flooring back to Northern Ireland and had it sandblasted to expose the grain; it was then made into shuttering and backfilled with concrete.

Adjacent to the open plan living/kitchen/dining space is the couple’s master bedroom, which isn’t as large as you might expect; quite deliberately. “When we were sailing, I was used to sleeping in very compact little timber clad cabins with everything stowed away. I wanted to recreate my memory of that.” The timber flooring continues up the wall to create a headboard and a small window has been created in the solid gable overlooking the church. A small wood burner adds extra comfort in the winter.

The bedroom is accessed by a large sliding door, an idea that first surfaced in their previous house. The door leaves are made from two pieces of MDF sandwiched together and fitted with a sliding mechanism which Jane sourced from Hafele Sliding Gear. Another nod to life on the waves is the rope handrail on the staircase, which Jane had designed by Rope & Splice.

Throughout this project, Jane has had her eye on every single detail, but how does she feel now about the experience of moving from architect to project manager to site foreman? “It was a big undertaking. You have the total responsibility for absolutely everything in the chain, from ordering the materials to getting things built correctly.”

She adds: “I now appreciate when a contractor says to me there’s been a delay on something, it can be down to various things; poor ordering, poor chasing, the weather, a transportation failure, or the order’s wrong when it arrives. You see everything more in the round, and you also realise how much you don’t know.”

In the words of one of her builders, there ‘may be a lot of building’ in Jane’s home, but she and David have turned a brownfield space in a conservation area into a place that they love, and one which genuinely complements its surroundings. Feedback from the community has been positive, and Jane also hopes that it’s paved the way for more self-builders to experiment, and “ask for more from their architects and builders.

She says it’s an instructive process for any architect: “Building your own house is an apprenticeship in all aspects of building, and I would recommend every architect to do it at some point, and the earlier in their career the better.” She’s now completed four such homes, but admits that Origami Studio has been the hardest, because of the extra roles she took on. She concludes: “I imagine it’s a bit like skydiving – thrilling at the time, but I’ll not be doing it again!”