A world-class multi-storey skate park has been constructed in Folkestone, Kent, a novel concrete form also designed to attract climbers and boxers, and which has quickly become a popular local landmark. Jack Wooler reports

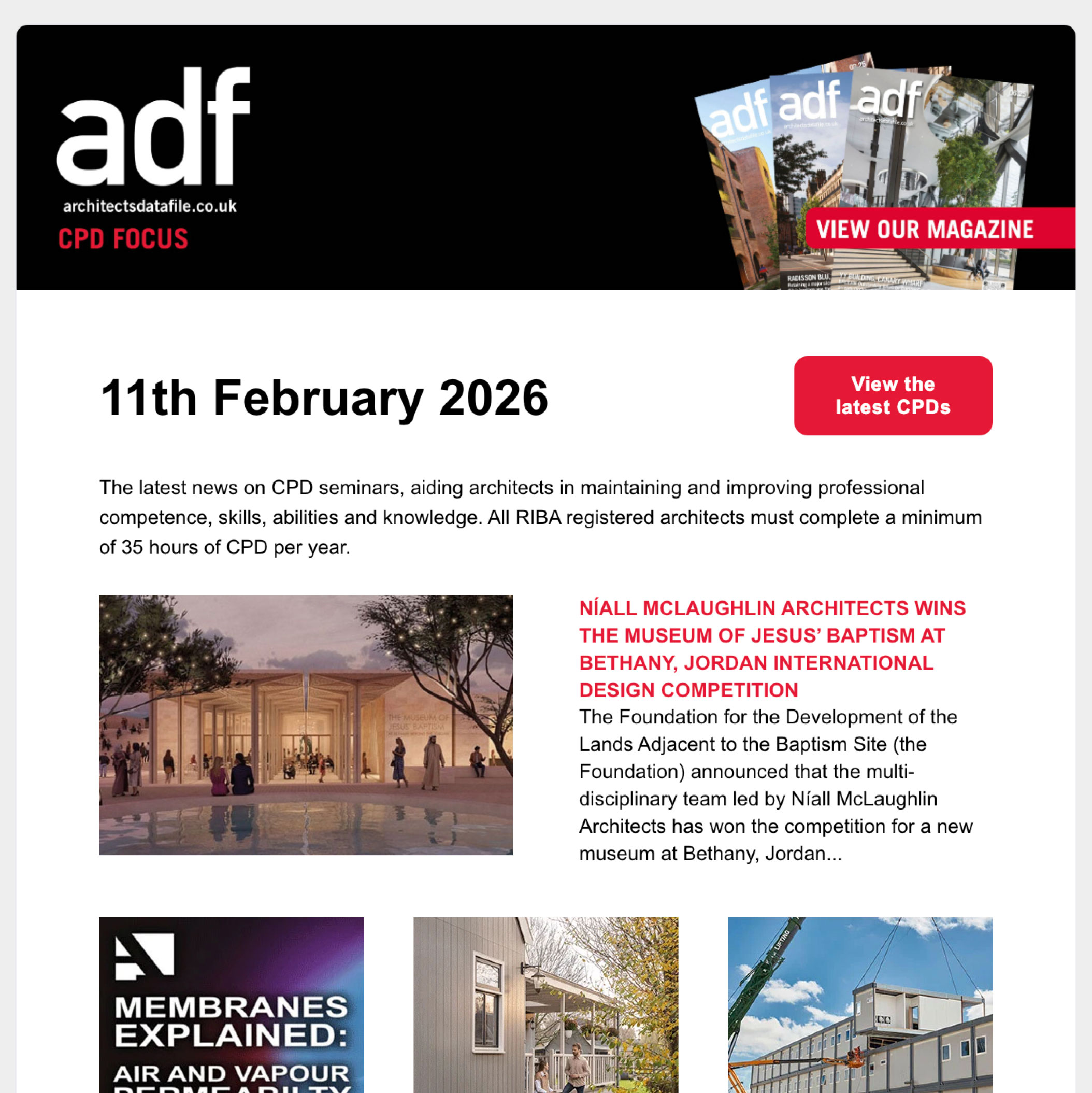

F51 is a multi-storey, state-of-the-art sporting facility in Folkestone, Kent. As well as three floors of skate park, the unique building offers a boxing facility, cafe, and competition-grade climbing wall that reaches up and around all of these spaces. It is claimed by its project team to have not only the world’s first suspended concrete bowls for skateboarding, but also to be the first multi-storey skate park.

The project was originally intended to be a car park, but the project’s main benefactor, philanthropist Sir Roger De Haan, worked with Kent and London-based architects Hollaway Studio to transform the scheme into what it is today. Floor by floor, the space allocated to ‘skateable’ areas gradually increased, until the project stakeholders collectively agreed that the entire building should be devoted to a variety of community facilities.

Hollaway Studio have an office in the neighbouring town of Hythe, and the scheme was built by contractors Jenner, who were founded in Folkestone. The building was a passion project for its multiple local contributors, and Roger De Haan, son of the late Sidney De Haan, founder of the Saga Group. Roger’s goal was to give something back to the area, it having brought his family such success.

Now complete, F51 is a strong and slightly conical form, increasing in width as it ascends skywards, providing the town with a dramatic focal point that both maximises its usable space, and creates an unmistakable and unique landmark for the area.

As a result, the project has quickly become popular, not just among the locals (with children in school in Folkestone having a subsidised entry fee of £1 a month), but for pro skaters and visitors alike who come from across the world to visit the facility. There has also been wide media attention from those inside and out the sport.

F51 is a testament to the passion of all its contributors, including a varied number of creators that provided artwork and expertise to create a space that closely meets the needs of its different users.

Approach

Walking to F51 from the seafront, De Haan’s work to regenerate the area is everywhere. They range from the beachfront itself, on which a major residential redevelopment of the area – also by Jenner – is well underway, to the vibrantly coloured commercial spaces linking to the town centre. The latter – also owned by De Haan – are rented out at subsidised rates to encourage cultural endeavours in the area.

According to the locals, the area has changed to be almost unrecognisable over the last 10 years, in no small part due to Sir Roger’s influence. And his regeneration projects have helped add a sense of safety, as well as of prosperity, to the area. To a new visitor, this is strongly evident as you pass through the welcoming and rejuvenated streets towards the town centre.

The feeling extends all the way to F51 itself. In contrast to most skate parks, which tend to be located on the outskirts of residential areas (and as a consequence, because they are not managed, can become territorial), it is located right in the centre of the town. That was the result of a clear decision by the project team to bring users into the heart of the community, instead of marginalising them.

Approaching the building on foot, with busy thoroughfares on either side of it, the striking parallelogram of F51 appears as a fairly massive form. The volume, relatively compact at its glazed ground level, is clad in crushed aluminium in a triangular pattern above, specified to weather the harsh coastal air. It is 6 metres wider by the time it reaches the top storey.

Even from outside, its function is clearly expressed, the concrete bowls of the first floor protruding out from the facade, and glazing providing glimpses inside. Also giving a signal to its use, the black painted ground floor is covered in graffiti from renowned artist Mr Doodle, who included various allusions to the building’s functions – as well as a reference to Roger de Haan. My attention was also drawn to a drawing celebrating a particular ‘rad dad’ – a member of a parents skating class who visited the project as it was finishing.

Reception

Heading inside through glass doors, visitors are first presented with a reception area and cafe, surrounded by a wall clad in skateboards of varying designs, which are available to buy.

As part of a commission to paint artwork around the skate parks themselves, almost every contributor whose art wasn’t included on the building itself were given one or more boards to design – and they would receive a portion of the proceeds.

Looking up, you see the undisguised forms of the colossal concrete bowls, suspended directly above your head. Even from below, their scale is impressive – obvious not just in the depth to which they extend from the ceiling, but in the massive concrete columns holding them, and the further floors, up.

Next door to the reception are a range of supporting facilities such as storage, bathrooms and changing rooms (also located on upper levels), as well as stairs and elevators up, and doors that open to a space dedicated to boxing, which is a popular pastime in Folkestone.

Inside this space is a full size boxing ring and an adjacent training room; the connecting sliding doors in between opening up to create one large entertainment space. This means that it can offer not just boxing practice, but other physical training sessions including yoga and pilates.

Suspended empty swimming pools

Climbing to the first floor – and away from the only heated portions of the building which are downstairs, for the comfort of the staff – double doors open up to the concrete skate park. Here, as on the remaining floors, it was decided the only ventilation needed was to regulate circulation, with users providing more than enough heat to keep warm. Because of this, all the interior specifications are graded for outdoor use, with the bowls essentially bringing almost all the servicing benefits of an outdoor space, but with the weatherproof practicalities of a roof.

As with all the skating floors, the space has been designed in conjunction with local skaters and experts to be of world class standard. And, according to its pro users so far, it has been a real success on this front. It also features designs from competition-winning local artists.

According to Maverick Skateparks, who designed the skating areas, the bowls were modelled after the empty swimming pools skating scene that began during a drought in California. Largely influenced by scenes from the LA skateboarders from the well-known Dogtown and Z-boys documentary, this floor is intended as a tribute to this piece of skating history, including some intricate tile detailing to its rim.

The most demanding floor to skate in terms of skill level, the bowls are very steep (I can vouch for this – they were tricky to climb in and out of on foot!). They have further protruding ‘lips’ and a faster, but less forgiving, surface than most skate parks.

In order to achieve the bowls’ complex construction, Maverick created an intricate 3D digital model to aid installation, and specialist firm Cordek were engaged to manufacture polystyrene moulds that

acted as the falsework for the bowls, delivered to site in eight articulated lorries and pieced together. Cordek says the rebar concrete reinforcement process was “incredibly complex,” every bar being positioned individually prior to a spray concrete mix being applied. It reportedly took six weeks to design and schedule and a further four weeks to fix into place.

While a traditional concrete slab would be poured continuously, the bowls were marked into sections completing one per day, being identified as the most economical approach without any compromise on the quality required.

Social climbing

From the same floor, users can also access the climbing wall and bouldering spaces. Claimed to be the tallest climbing venue in the south east, the walls of the main climbing wall reach up to 15 metres – carving a space up through all remaining floors, with glazing connecting the spaces visually.

Here, the main wall also includes two dedicated speed climbing sections, with auto ‘belays’ and speed timers to test speed and endurance – as seen in the Olympics – with coloured footpads throughout to cater for a range of physical abilities.

Nearby is also a further free-climbing bouldering space, with soft flooring and lower heights, meaning users don’t have to be strapped in. These multifaceted surfaces offer varying angles and over 230 m2 of surface with a multitude of routes and features for climbers to tackle, including steep overhang roof sections, catering for beginners through to experts.

Patchwork of timber

Continuing the climb through the building (which can be made on foot or up the walls!), the next two skate parks are revealed on floors two and three, each bigger than the last as the building grows outwards. All the walls on these floors lean outwards, which assists skaters who will often come into contact with them. Further helping them, the windows are shaped to be smaller at the bottom, reducing the chance of them running into them, and are reinforced throughout with wire netting, to reduce the chance of cracking.

Created to get progressively easier to skate upon, the second and third floor skate parks – (‘flow’ and ‘street’ parks, respectively) – are built from timber. It is of course a more pliable surface, and was designed using a heavily CAD-oriented process led by Cambian Action Sports.

According to Cambian, both of these floors provided significant challenges. For one, most skate parks are of course in rectangular clear span industrial buildings or outdoor spaces – meaning here its designers had to consider not just the shape of the building, but the presence of the columns and the circulation of the building in use.

Overcoming these challenges however, the finished result is a combination of two further unique skate parks, one providing a simpler, pedestrian streetscape that provides varying routes and interplay between its users, and the other creating infinitely long continuous smooth lines, where skilled riders can venture anywhere they wish.

On both of these floors – encompassing over 1,500 m2 of skateable timber floorspace – the sustainably sourced plywood has been intricately connected in a patchwork to combine what the designers believe to be the ideal combination of speed, safety, durability, aesthetics, as well as a potential for upgrades as trends evolve.

One particularly impressive element of this patchwork is on the fluted columns of the second floor, in which Cambian took several thin sheets of plywood, bent them, and glued them in a press to form the curved shape.

Community

Now in frequent use, the project is demonstrably a huge success.

Opened in a post-Covid world, F51 quickly became more important than could have been conceived when the original ideas for a car park evolved into what became this state of the art sporting facility.

At such a pivotal time, when young people have desperately needed freedom and accessible space to safely expend their physical energy – and return to having some fun away from screens and pandemic-induced isolation – this facility has turned out to be of huge benefit.

Despite the innovation in its form, it is in its contribution to the community, and the community’s returned passion for it, in which F51 truly shines.

Guy Hollaway, who is principal partner at Hollaway Studio, summarises this perfectly: “F51 is about investing in the next generation, to help regenerate Folkestone town centre – this building puts young people first, and for the first time, architecture, engineering and the skating world have come together to create this truly unique design solution.”

He continues: “Since the opening, we have seen both the local community and enthusiastic skaters from further afield engaging with the building. We hope that this building will not only inspire and foster young minds but could also help to facilitate the next Olympic skater.”

Similarly, Ella Brocklebank, head of communications and business development at the contractors on the scheme, Jenner, echoed Hollaway’s sentiments, describing the wider impact of the project: “A sustainable future in its truest form is where the young are nurtured and given the opportunity to grow and fulfil their potential; to gain new skills and achieve great things.”

She continues: “The aim is simple, a common sense approach to invest in this generation, with the aim that it will go on to invest in the one that follows – generational regeneration.”

“Undoubtedly,” Ella concludes, “this is the life blood of F51.”

Local legacy

F51 is a one-off, and is a project that every one of its contributors are extremely proud of, and building that’s a product of its function which has instantly become a landmark.

Combined with this passion, it has quickly garnered real success through enabling both its future users, and the experts that put it together, to have true freedom in designing the building to an uncompromisingly high standard.

It is clear that this highly unusual project could not have been realised without the substantial donations of Sir Roger de Haan, which was something that everyone I met appeared truly grateful for. The finished result is an example of what a leisure project of this type, designed ‘without constraint’ can deliver.

If de Haan’s aim was to create a legacy for himself by investing in the current generation, by giving the town’s young people a reason to stay in Folkestone, he has absolutely achieved that with this groundbreaking scheme.